This paper is written as a response to feedback and discussion following a presentation by the author at the 2009 Future Places Festival in Porto. The synopsis of the presentation was:

“Phil Taylor will discuss the integration of constantly evolving digital media practices and applications within the creative environments of higher education, specifically focusing on moving image and video. How this medium is taught, how it is employed, and how it is perceived by both tutor and student, underpinned by the main question of what are the broader cultural implications of using contemporary digital media within the curriculum?”

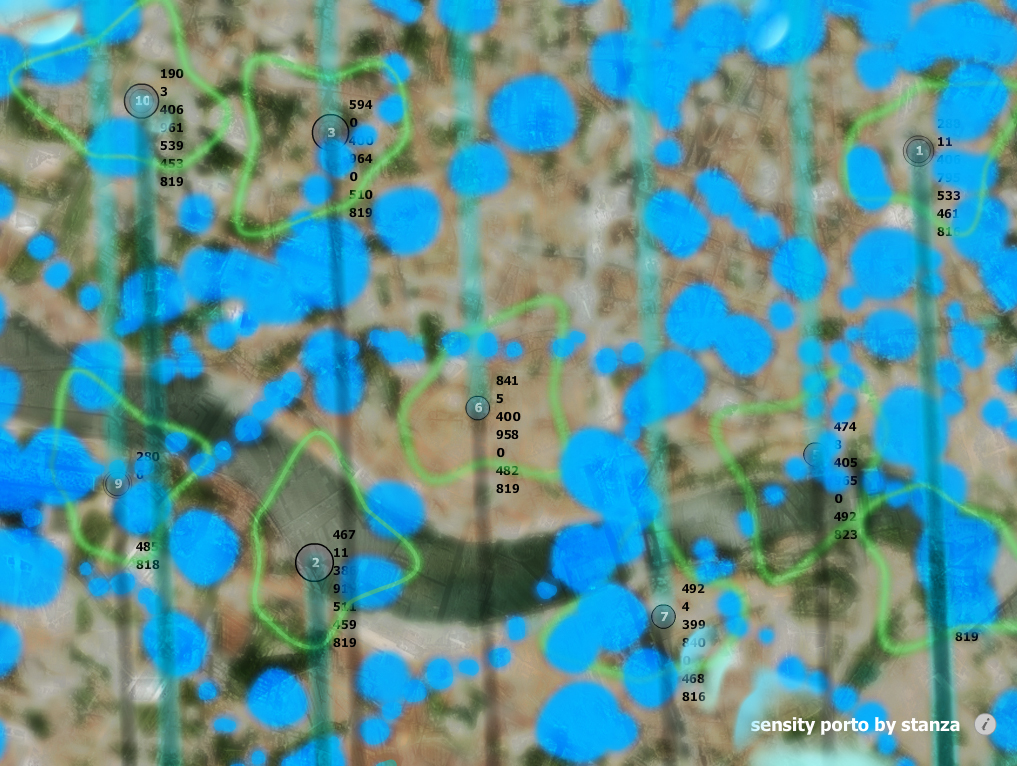

All the artists that were selected to present their work at the festival employ digital media as an integral component of their working methods and creative processes. The festival, jointly organised by the University of Porto and the University of Texas (Austin, USA), focused upon the question of how digital media in the creative arts interrelates with local cultures. Heitor Alvelos (festival co-curator and head of Communication Design, University of Porto) wrote in his introduction to the 2009 event: “If digital media can do so much for global communication, knowledge and creativity, how can it contribute to local cultural development?” The array and diversity of participants in the festival is testament to the interest and relevance in this area of debate, practice and research within sociological, ethnological and pedagogic frameworks.

The paper presented was part of a one-day conference on the theme of ‘creative uses of digital technology in curricular environments’, relating to the broader festival theme of ‘aspects and strategies of contemporary digital media and its impact on locality’.

A previous collaboration in a joint University of Brighton and Royal College of Art research project had informed the content of the paper. The project is entitled ‘Bridging the Gap in Moving Image: connecting new and traditional technologies for enhanced communication between students, academic and support staff across art and design’. The three main points presented in this project were: 1) Analogue versus digital in the creative process. 2) ‘Impatience’ – the gap between expectations and experiences regarding the time involved in learning and teaching moving image. 3) What are the broader cultural implications of using contemporary digital media and technologies within the curriculum?

During field research for the project it became clear that the ‘Lo-Fi’ phenomenon within the application of analogue and digital technologies as part of the creative process was both topical and very much debated amongst staff and students alike. The single most clearly identifiable research outcome was the level of debate and multifarious points of view and opinions expressed by those involved in education as well as the professional world regarding the role of the ‘analogue’ in a predominantly digital world, primarily in process and method applications.

The term ‘Lo-Fi’ encapsulates a complex phenomenon within the many and varied working processes that are integral to the creative outcomes within art, design and music (the term itself is a derivation from the acronym ‘Hi-Fi’ meaning ‘High Fidelity’ in music production terminology). It is commonly used to define ‘low quality’ in aesthetic and aural references, and in comparison to digital processes, analogue equates to low quality.

Undergraduate students at the University of Brighton, particularly those of a younger generation, are not drawn to using the latest technology in perhaps the same way that practitioners who received their degrees in the pre-digital 1980’s era are? These students are not impressed by how fast something can be achieved digitally, or how efficient personal computers are today. A mention during tuition of the difficulties and long drawn out process of digitising film by harnessing the most powerful computers at that time (that cost upwards of £20K) is met with a polite indifference, as if the invention of the steam engine was being discussed in great detail. For them, today, the ease of use of digital technology and self-publishing is a given.

They have grown up with computers, they already know what the Wizard of Oz looks like, and which levers he pulls before the story begins. They are increasingly interested in the analogue, the 16mm Cine film, the old typewriter etc. At the University of Brighton there is a fully equipped traditional letterpress facility – it is one of the most popular resources in the building with students from a variety of disciplines.

In light of these findings the research generated two main questions:

– Why are students in the creative arts currently so intrigued by ‘old’ technologies?

– Do educators see a gap between the old and the new, where students do not?

Some of the answers may be found by looking away from the education environment towards popular culture and the Internet.

We all have heroes – as an undergraduate Fine Art student, mine were the filmmakers Wim Wenders, and Jim Jarmusch, and the painters Stephen Campbell and Adrian Wisniewski – AKA ‘The Glasgow Boys’. The heroes my students cite today are Mike Mills, Shepard Fairy and Ed Templeton – AKA ‘Beautiful Losers’. These ‘non-art trained’ artists represent a counter-culture phenomenon – they consume popular culture and spit it back out in a highly idiosyncratic way that utilises an eclectic array of analogue technologies and working methods, and most notably, the art of self-publishing. One can trace that line back to Andy Warhol of course, but the DIY approach to using the tools of creativity seems to resonate with our young, eclectic creative individuals today (who can all self-publish with ease).

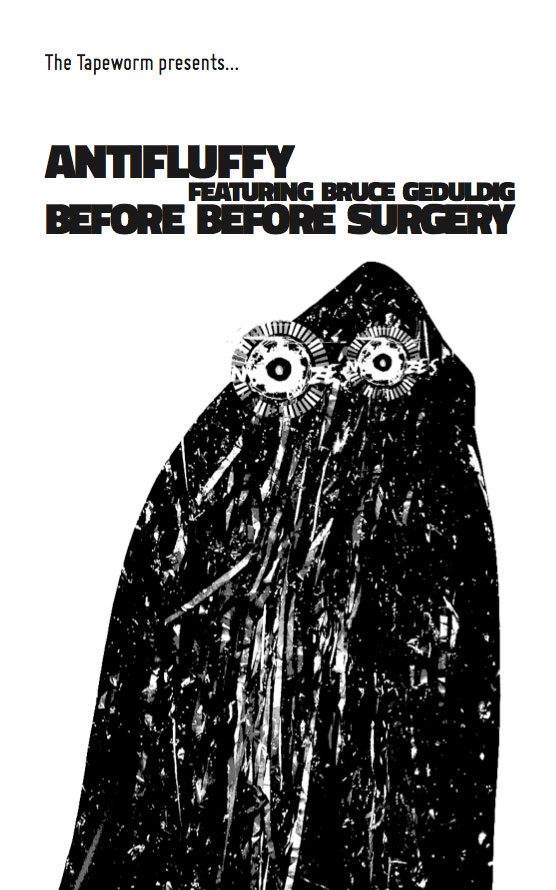

There are no barriers to reaching a wider audience, the mass reproduction of art works and self-expression through digital technologies means that for the ‘iPod’ generation, the magic of the digital does not matter – the alchemy of the analogue is more unpredictable, and therefore more alluring. The same can perhaps be said of music and self-publishing. An iPhone App can become a self-contained digital recording studio, which can be employed with relative ease and the results uploaded to Last FM or any of the myriad of music-sharing web sites. The process is fast, professional and requires no intermediary to hinder the drive for personal self-expression that characterises the current generation of aspiring musicians. Many bands and artists utilise the digital avenues available to them to reach a wider audience yet they also adhere themselves to analogue instrumentation and working methods that are idiosyncratic and regressive when compared to heavily processed digital recording methods and music tools. There is undoubtedly a draw towards the more intimate, and perhaps authentic, relationship an artist can have with his or her music making equipment that is located within the analogue realm.

This is echoed in the creative professional world with a noticeable trend for young illustrators and filmmakers to increasingly explore analogue animation techniques that are less polished in their aesthetic qualities than CGI. The popularity of these techniques in the commercial entertainment industry is also undisputed with the recent highly successful film adaptation of Roald Dahl’s book ‘Fantastic Mr Fox’ (directed by Wes Anderson, 2009) for example. One of the questions raised at the Porto conference was that if digital technology (over the last two decades) has increasingly precipitated a convergence of media and techniques encouraged by greater accessibility, ease of use and dissemination, why is there a currently a divergence of these in the creative and commercial world? This is evident in the contrast of Wes Anderson’s Oliver Postgate style treatment of a traditional narrative for the big screen with the recent release of the games company Activision’s technologically advanced digital game ‘Modern Warfare 2’ (2009). Both are set to be extremely popular, not just in a commercial sense, but also for their aesthetic visual styles and application of technique. Both employ narrative structure, yet one is reaching back to the analogue past and the other leaping ahead in digital super-realism.

‘Impatience’ is a topical term in our digital age, the (Utopian) expectation is that digital technology will help us to live our lives in a more fluid, efficient manner, thus freeing up more leisure time, whereas in reality we experience information overload via a mass of digital technologies that pervades our societies public and work spaces. During the research project a number of interviewees expressed impatience with digital technology (the ‘tyranny of the email’ for example) and constant pressure to upgrade and keep up to date.

Perhaps one of the reasons why art, design & music students are interested in analogue ways of working is that the software and hardware industry uses a relentless ‘upgrade me’ approach to sell their products – the latest version is always going to be better, faster – therefore an ‘expectation’ is built into the use of that product (as with new technology in a broader sense), and invariably, it will disappoint to some degree. For example, the students’ real world experience of ‘real-time’ rendering within video editing is not ‘real-time’ at all .. so the expectation is not matched by the experience and impatience creeps in and alternative methods and technologies sought.

One cannot be impatient with a celluloid film inside a lightproof film camera – the medium itself has a time-delayed outcome.

As a lecturer in digital media I am not impatient with a video-editing programme such as Adobe’s After Effects, because I know how slow, expensive and difficult it was to create the same results fifteen years ago. But our students seem unaffected by this admiration of ‘new’ technology. They can, however, apply ample patience sitting in front of an old, poorly operating typewriter to achieve their as yet unresolved, unpredictable outcome that may involve ‘happy accidents’ along the route and a chance of alchemy.

Perhaps, for the curriculum, software and hardware manufacturers are concentrating too much on this ‘upgrade me’ approach, the performance of the tools, what they can do rather than what they can’t do. An old film camera is challenging and perhaps arresting as part of the creative process because of its limitations – what it can’t do contributes to the process and the outcome. When the Kodak Company stopped manufacturing Polaroid film in 2006 an Internet based community grew up to fill the gap in what was perceived as a worthwhile medium to continue using in creative photography; today there is a collectable status for vintage Polaroid equipment, although it is hard to use with inconsistent results the desire for the ‘authentic’ in the medium is driving the resurgence in interest in instant film types.

What are the broader cultural implications of using contemporary digital media and technologies within the curriculum?

In an age where digital self-publishing is ubiquitous, who are the arbiters of taste? Who are the gatekeepers of artistic merit? Of course there are the curators the panellists, the experts etc. But in popular culture the production and dissemination of virtual artefacts of self-expression is an exponential curve. Everyone and anyone can be an author, an artist, a musician.

What are the implications for our culture? Is this a welcome aspect of greater interconnectivity enabled by new technologies? If we look at the artists within the ‘Beautiful Losers’ group, despite their unconventional approach to creativity and their counter-culture stance, they all have benefitted from mass exposure via the internet and self-publishing.

The question is not whether the phenomenon it is good or bad, the question is irrelevant (that would be like imagining what our world be like without the mobile phone – impossible for the generation who have grown up with them) – it is the here and now and endemic in our lives. UK Art Schools used to provide favourable conditions and a fertile climate for the growth of non-conformist self-expression (witnessed by the many musicians who started their journey’s in a studio of a 1960’s Art School). That climatic environment has, now perhaps, moved beyond the confines of the Art School. The interconnectivity we all experience in contemporary mass culture has created a virtual habitat where distinctiveness is perhaps harder to locate, where a democracy of taste prevails, where there are ‘cells of activity where distinctiveness can be found’.

When I first became interested in the emergence of the Internet and digital technology, the term ‘MUD’ (multi-user domains) used to intrigue me in a sociological and anthropological sense – it made me think of small communities living in mud huts, isolated from each other – the opposite of what the term means. Now, with our ability to interconnect with each other in vast virtual communities are we really any closer to each other? Is what we create more personal and authentic because we communicate and self-publish with ease?

Mike Mills produced a T-Shirt in the early stage of his (what now can be defined as) career that had the phrase: “Fight against the rising tide of conformity” printed on it. This image can be downloaded an infinite number of times from his web site.

Most of the ‘Beautiful Losers’ artists are now very well known and are regularly commissioned to produce high-profile advertising campaigns (Fairey created the Obama election image). The irony is that a major contributing factor to their notoriety is that they all exploited digital self-publishing, despite employing working methods and resulting artworks that are very definitely ‘analogue’ and non-conformist. This would suggest there is an intriguing contradiction and dilemma in this phenomenon. Many artists and designers are immersed in digital technology, if not in the creation of their work, then its dissemination. But because ‘anyone can do it’, there is no distinctiveness, no gatekeepers and no rebels, because the medium is ubiquitous – it is not edited, curated or selective. This is one of the main challenges for the Creative Arts and Industries operating in the new digital millennium

Phil Taylor © 2010

——————————————————————————————————-

Phil Taylor is an Educator, Artist and Musician based in Brighton, UK.

www.hotelvitrine.com

http://artsresearch.brighton.ac.uk/research/academic/taylor_phil/

http://www.atomgrad.co.uk