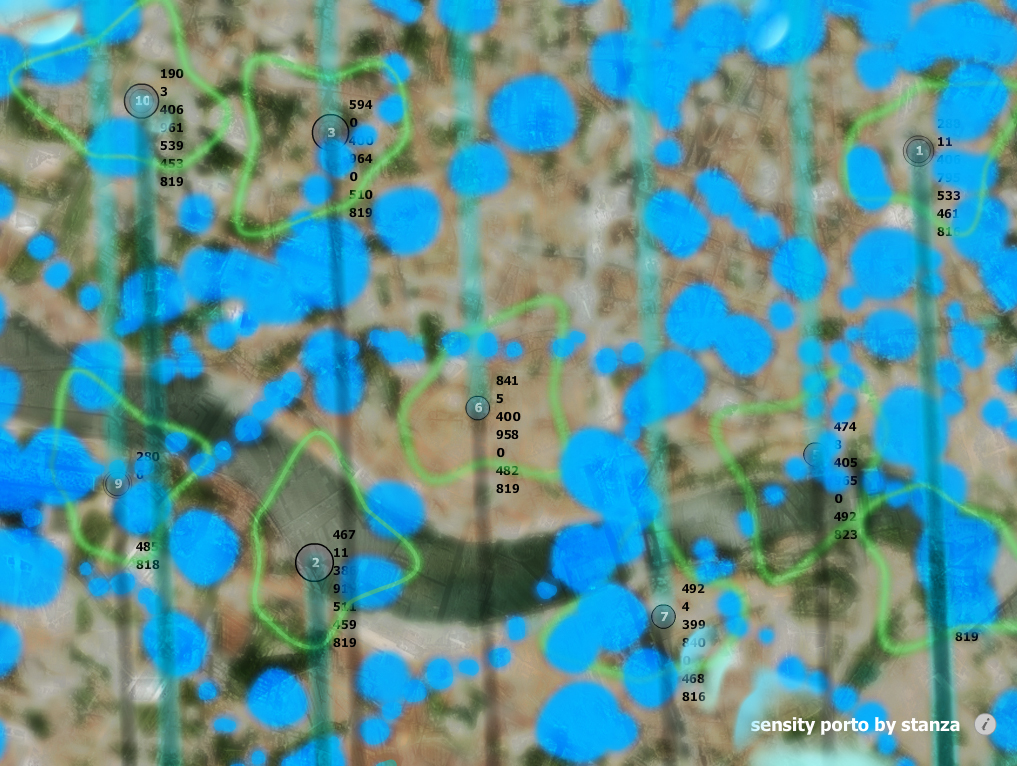

The following is the text of a lecture I gave to the assembled masses of the Future Places Festival in Porto, Portugal, October 16, 2010.

Blaine L. Reininger

I want to talk today about aleatoric music and the use of chance operations, or “Chance Ops” in the creative process in general. Aleatoric music , from the Latin “alea” for dice, is defined by Wikipedia as “ music in which some element of the composition is left to chance, and/or some primary element of a composed work’s realization is left to the determination of its performer(s). The term is most often associated with procedures in which the chance element involves a relatively limited number of possibilities.”

The use of random variables applied to systems to obtain creative results in the arts rose to prominence in the 20th century, although there are historical examples, most notably the Musikalisches Würfelspiele (“musical dice games”) of the 18th century, the most famous of which was attributed to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Randomly generated content was most famously proposed by the Dadaist Tristan Tzara who proposed a system of writing random verse in 1916:

To make a Dadaist poem:

• Take a newspaper.

• Take a pair of scissors.

• Choose an article as long as you are planning to make your poem.

• Cut out the article.

• Then cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them in a bag.

• Shake it gently.

• Then take out the scraps one after the other in the order in which they left the bag.

• Copy conscientiously.

• The poem will be like you.

• And here you are a writer, infinitely original and endowed with a sensibility that is charming though beyond the understanding of the vulgar.

-Tristan Tzara

These methods were also adopted and modified by the Surrealists, notably Andre Breton, and Phillipe Soupault. Such methods as automatic writing and drawing became part of the surrealist canon.

Chance operations and their underlying philosophy only found their way into music later and were made most famous by Charles Ives, Henry Cowell, his pupil John Cage and by Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez and others.

John Cage’s Music of Changes (1951) is the first piece to be conceived largely through random procedures”

Many among the neo-dadaist trend in “alternative culture” and rock which began in the late 60’s with such groups as Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band and Frank Zappa continued down the trail blazed by these pioneers, though often with greater good humor than the stony-faced Surrealists and Dadaists. This same thread continued on the fringes of punk rock and new wave. Brian Eno’s “oblique strategies”, the work of Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire, The Residents, and even that of Tuxedomoon draw from the same hallowed Dadaist sources, including the desire to mine the collective unconscious through random creative systems

The incorporation of random elements into the arts arose in an attempt to bypass the desires of what Freud calls “ego” and what Buddhism calls Samsara, the petty promptings of a limited system of perception, and reach a transcendent and powerful syntax which not only describes, but is part and parcel of the universe itself. Chance operations confound and bypass the quotidienne and the mundane in much the same way as the Zen koan.

“nothing is accomplished by writing a piece of music

nothing is accomplished by hearing a piece of music

nothing is accomplished by playing a piece of music (Cage 1961:xii)”

Throughout the ages, men have attempted to foretell the future by casting stones, or coins, or dice, or sticks. By observing the effects of decisions made by an extra human agency, that force which determined the fall of the dice, chance, fate, karma, the Tao, it was felt that the workings of the universe itself could be observed. The invisible could be inferred by its effects upon the visible, a feather launched into the wind, a stick cast into a river.

Although the results of these fortune-telling experiments can be fascinating and even educational, especially when applied to the arts, their true importance lies in the attempt by the experimenter to understand the universe, its purpose and his own relation to it.

What is important for the artist is not the work itself, or its perceived value, it is the extent to which the process used to achieve the results fosters his evolution and allows his perception to become unclouded by petty desires and disappointments.

My own take on the work of Cage and others is that, while the theory and philosophy behind it is sound and evolutionary in nature, the results are often spare and joyless. I believe that is is possible to use these aleatory techniques to achieve results that are aesthetically pleasing and even entertaining even for those not steeped in the underlying theoretical background. I have attempted to do this in my own work and I admire those who walk this same path.

Thank you for your attention and all the egg yolks.

Some links:

- Mozart’s dice game

- Randomness Page on my site:

- Wolfram Tones a really fun music generator.