In 2008, futureplaces was created as a venue for exploring how digital media can support local culture. The past two festivals have hosted installations and performances that have approached this topic in a variety of ways, from different geographic, cultural, and artistic perspectives. The festival program itself has changed over time as we playfully investigate new ways to interpret, celebrate, and interact with the local.

Digital media is often conceptualized as an ephemeral, “space-binding” communication medium, to draw upon Harold Innis (1951). This space-binding quality, according to Innis, fosters the building of empires, as the ideas and images of dominant political and cultural structures are spread globally. These media bring authors and viewers together across wide expanses of geography, potentially encouraging cultural homogeneity through well-promoted blockbuster films that can be streamed around the world, global advertising campaigns, or social network applications like Facebook that attempt to culturally interpellate users in particular, predetermined ways. Online political activity is also suspect: Websites and blogs may encourage a profusion of animated discussions focused on the issue of the day, but does daily online debate translate into sustained offline activism or is it merely a simulation of participation?

At the same time, digital media has empowered a diverse flowering of authorship, allowing creators around the world to mold images and text in new ways and make their work available to anyone with an online connection. While traditional broadcast technologies have historically been limited by spectrum scarcity and huge infrastructure expense, digital media production is hailed as a way to bypass these hurdles and create sophisticated content, directly communicating with the world from one’s PC, laptop, or mobile device. The flexibility of digital media encourages new forms of production, participation, and consumption to emerge. This ability to publish works, perspectives, and opinions is not equal, however, but is still determined by issues of access including infrastructure quality and online cultural capital—the faculty to reach out to audiences and employ social networking sites, mobile technology, and engaging design.

Futureplaces complicates and interrogates these conceptualizations, experimenting with different approaches, venues, and themes. Every year’s program has been marked by its diversity, but each year has also had common themes. In 2008, the festival began by looking at how digital media has been approached in academia and in other media festivals. Representatives of the Transmedia program at the Sint-Lukas Academy of Brussels and MediaLab Helsinki presented their curricula and student projects. The MAPA panel continued the mission of the previous year’s education conference, featuring representatives of different Portuguese institutions discussing how their programs are approaching digital media. Additionally, the first futureplaces hosted some of the best work from existing media festivals, such as U Frame and the Black&White film festival, and invited Pedro Custódio of SHiFT to discussion that festival’s approach to local culture. Many of the talks and exhibits of the brand new festival were hosted in University of Porto’s Rectory Building, which provided a grand beginning to the enterprise. This choice of venue also provided some wonderful visual contrasts, including festival attendees, surrounded by the stately trappings of traditional education, videoconferencing with a cultural activist in Brazil and discussing the uses of digital media in preserving community memory.

The first production of futureplaces was fortunate to take advantage of other rich, diverse sites of Porto culture as well, including the world-renowned Casa da Música concert hall, the Serralves Foundation, STOP, a musicians’ space converted from a former shopping mall, the Passos Manuel theater, and Maus Hábitos, one of Porto’s foremost venues of the local arts and culture community. The latter two spaces hosted most of the festival’s 28 finalist exhibits, many of which came from Portugal and the United States. The first top prize went to Filipe Pais’ “Living Room Plankton,” a project featuring an artificial organism than responds to environmental stimuli. Pais’ work examined how digital media allows new forms of interactivity, and offered a highly innovative exploration of self/other boundaries—a microcosm of the negotiations and dynamics that evolve within local culture. Other significant work appearing in 2008 included Shlomit Lehavi’s “Time Sifter,” an interactive installation incorporating traditional cultural artifacts and new technologies to explore how we experience others’ memories, and Rudolfo Quintas’ “Burning the Sound,” an interactive sound performance focused on emotion, ritual, and control.

The 2009 festival focused its geography around the Passos Manuel neighborhood, drawing upon the area’s existing cultural energy while effectively creating a temporary “local culture.” While the festival included concerts at the Casa da Música and talks at the University Rectory Building, the focus of the festival exhibitions and interactions largely shifted to Maus Hábitos and the neighboring Passos Manuel theater, as well as another memorable evening at STOP. This tighter organization of space offered participants greater opportunities to socialize and take part in planned and ad hoc discussions and performances, while experiencing an established, culturally active neighborhood of Porto.

The festival featured fewer entries in 2009, with 15 finalists being invited to exhibit. First prize was awarded to Brian Cohen and his team at TRAX Arts, an arts company based in Melbourne, Australia. Cohen’s team presented “Outhouse” a portable lavatory re-fitted on the inside to resemble a tiny Victorian drawing room. Within this intimate atmosphere, participants were invited to seat themselves and react to a series of questions on video, giving insight into their memories, expectations, and personal philosophies. This confessional booth was only semi-private, however, in that participants could choose to make their responses available to all, on an outside screen. Like Lehavi’s 2008 installation, Cohen’s piece incorporated historical, “analog” references, employing them as cues to trigger emotional memory, while also investigating the lines drawn between personal and public: How do we produce meaning from another person’s expression of local culture, and from another’s personal or community memory? Second prize went to “Oporto-Brooklyn Bridge” an interactive sound installation created by New York-based artists Naomi Kaly and Alyssa Casey that drew on recordings created at two landmark sites of transit.

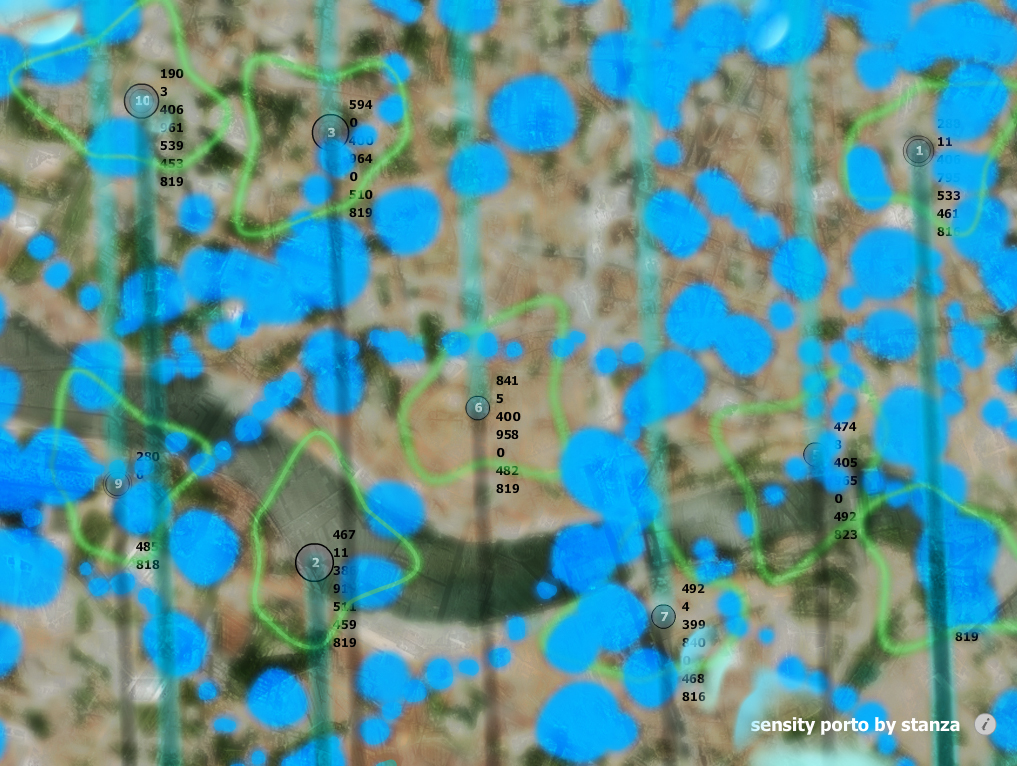

While the geographic scope of the festival activities was tightened and the number of finalists less than in 2008, the opportunities for participation in 2009 grew, with more speakers, including local digital media students, and with more workshops, including three that addressed different aspects of location aware devices and mobile technologies. Nuno Correia and Mónica Mendes reprised their well-subscribed workshop on interface design for mobile devices, while Valentina Nisi and Ian Oakley led participants in exploring the construction of interactive mobile narratives and David Gunn and Guillermo Brown organized a mobile recording session across parts of Porto. Golan Levin’s two-day intensive on Computer Vision also proved extremely popular.

In 2010, months of work are about to culminate in another intense five days of workshops, discussions, performances, and parties. This year continues some of the trends from 2009, focusing many activities within the creative space of Maus Hábitos and the surrounding area. The 2010 workshop opportunities reflect the festival’s continuing commitment to the innovative use of mobile technologies, through sessions on mobile application development, narrative experiences via mobile devices, and mobile radio streaming. In addition, MediaLab Prado’s workshop on “neighborhood science” explores opportunities for new forms of civic involvement and community participation, themes that take the festival closer to one of its sister programs, the International School on Digital Transformation. While still a very young festival, futureplaces is addressing some of the most important digital media trends today from a variety of fresh perspectives. In doing so, the festival engages in the important activity of capacity building, creating an environment conducive to future opportunities for community involvement, artistic experimentation, technological innovation, and economic development.

Innis, H, (1951). The Bias of Communication. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.